Idisz Buch was a Jewish publishing house which operated in the years 1947-1968. Durning over twenty years of its existence, the house released 350 books. The published works were solely in the Yiddish language, which was supposed to foster the revival of Jewish culture in Poland.

It was six months after release of the first issue of Dos Naje Lebn newspaper, when an expatriate writer and poet Dawid Sfard, returned to Poland from the Soviet Union. Still during his residence in Moscow, he dreamed about opening of a Jewish publishing house. Mr Sfard, who used to work as the Secretary of the Union of Jewish Writers during the pre-war period, quickly re-engaged himself into cultural activity after coming back to his homeland. In 1946, he became Member of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland, Secretary General at the Jewish Cultural Society and Deputy Chairman of the Union of Jewish Writers and Journalists. In Autumn of the same year he fulfilled his dream and launched a small publishing project at “Dos Naje Lebn” in Łódź, whose main press title used to be “Jidisze Szriftn” (Yid. „Jewish Writings”).

In 1947, the publishing project in Łódź transformed into an independent publishing house known as Idisz Buch (Yid. “The Jewish Book”). One of the first publications released under the umbrella of “The Jewish Book” was „Ojf di churwes” (Yid. “On the Ruins”) by Chaim Grade, „Der mencz wet gut zajn” (Yid. “The Man will be Good.”) by Lejb Olicki and “Mit asz ojfn kop (Yid. “With Ashes on the Head”) by Awrom Zak. All these books were centred around the topic of the Holocaust, and the majority of texts had been written still during the war. In 1949, the publishing house was relocated to Warsaw. Until 1950, the custody over Idisz Buch had been held by the Jewish Cultural Society. However, in October 1950 the situation changed, when ŻTK i CKŻP merged into a new entity i.e. the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland.

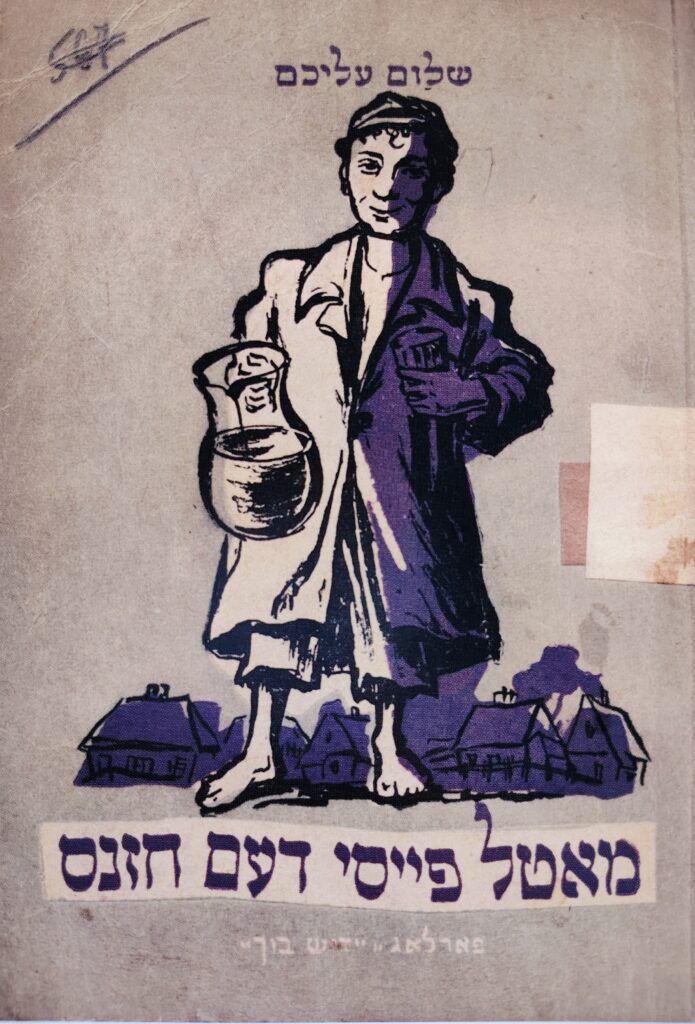

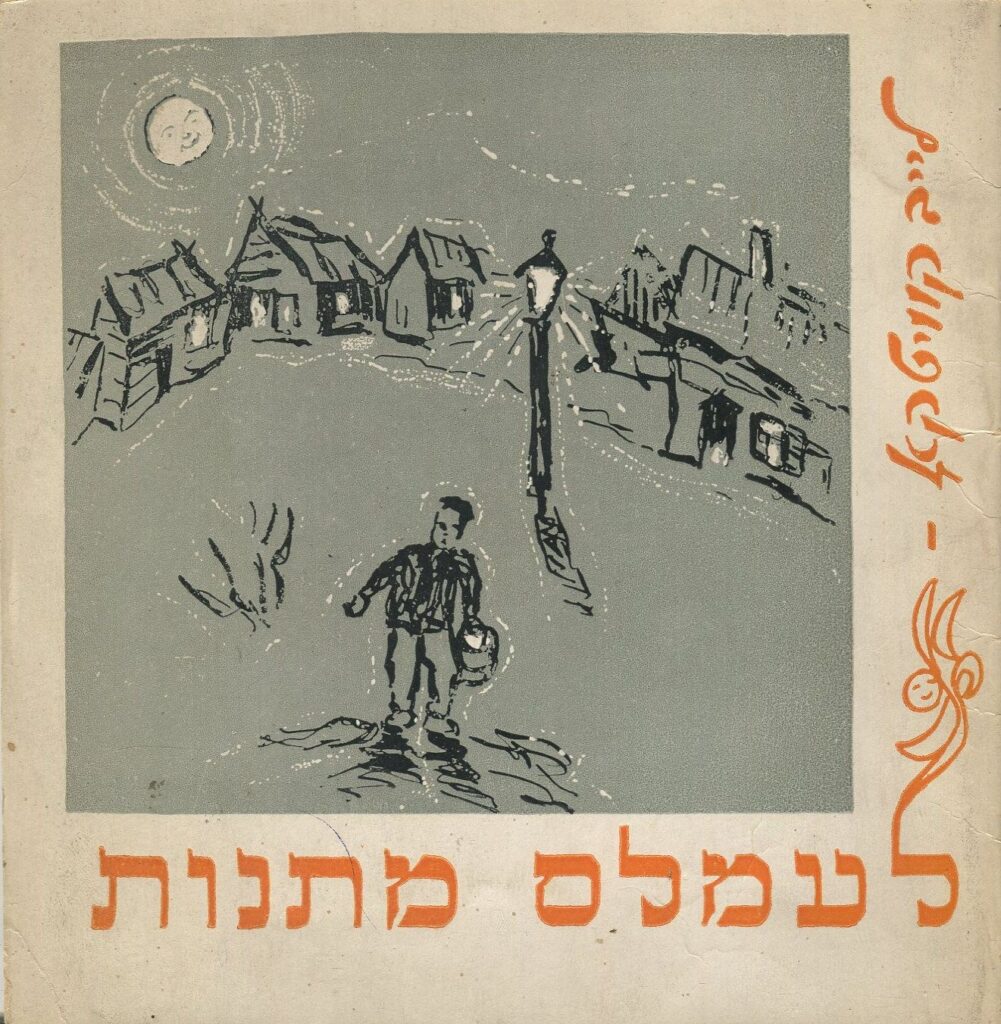

The nationalisation of Jewish institutions meant that Jews were the only national minority in communist Poland to have a press, theatre and publishing house in their own language. The nationalisation of Idisz Buch was very beneficial – thanks to state subsidies, between 1950 and 1955, up to 30 Yiddish titles were published annually. During this period, the thematic profile of the published works also expanded. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, in her article „A Few Remarks on the Idisz Buch Publishing House” distinguishes as seven subject areas: the Holocaust, works by classic Yiddish authors, works by contemporary Jewish writers (especially from Poland), the history of the Jewish people (with particular emphasis on Poland and the revolutionary movement), literature for children and young people, translations from foreign languages (including the Polish language), and albums and reproductions of works by Jewish artists. The range of literary works published at that time included for e.g. „Hejmerd” (Yid. “Homeland”) by Binem Heller, “Lider” (Yid. “Poems”) by Kalman Segal, and the translations of “Julian Tuwim far kinder” (Yid. “Julian Tuwim for Children”), or “Pan Jowialski” by Aleksander Fredro. At the beginning of the decade, the collected works of the classical Jewish writers i.e. Szolem Alejchem and Icchak Lejb Perec appeared on the publishing market.

In the years of its peak popularity, Idisz Buch had ca. 5 thousand long-term subscribers. However, after years it turned out that the actual number of those genuinely interested in Jewish literature was not as huge as the number of subscribers. Many of such them were obliged to purchase subscriptions as part of their workplace policies. The majority of readers, especially including the inhabitants of the so-called Regained Territories, complained about the oversupply of poetry, while there was a growing interest in fiction. However, the management of Jewish institution did not pay much attention to the readers’ opinions. We have Jewish writers from various genres and we cannot tell a writer how to write – reads the minutes of a meeting of the Jewish Cooperative ‘Zgoda’ in Wrocław – One should get to know poetry, even though it is a little more difficult.

During the so-called Polish October in 1956, the Polish supporters of the Stalinist regime attempted to shift responsibility for the previous lawlessness onto political activists of Jewish origin. As a result of these efforts, anti-Semitic sentiment began to rise in the country, causing many Jews to decide to emigrate. Among them were not only readers, but also authors of books published by Idisz Buch. Despite a significant decline in the number of subscribers, the publishing house did not suspend its activities. Regardless of the anti-Jewish sentiments prevailing among communist party members, the authorities continued to provide financial support to minority organisations. This helped the publishing house to survive on the market.

At the end of the 1950s, mass emigration came to an end, which stabilised the number of readers of Jewish books. In the new decade, Leopold Trepper, then president of the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland, became the head of the publishing house. Shortly afterwards, Idisz Buch started cooperation with foreign-based publishers including for e.g. International Yiddish Cultural Movement (IKUF), New York. In 1961, the first volume of Emanuel Ringelblum’s “Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto” was published, and two years later, on the 20th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the second volume was released. A year before the closure of the Jewish publishing house, books published under its auspices reached 24 countries.

The anti-Semitic campaign, which reached its peak in March 1968, led to the mass emigration of the Jewish people and their marginalisation in both social and professional life. The authorities closed Jewish schools, most Yiddish-language magazines were shut down, and the activities of the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland were severely restricted. A similar fate awaited Idisz Buch – most members of the editorial team left Poland, and as a result, after more than 20 years of activity, the publishing house ceased to exist.

By Marta Rydz

Next month, we will publish our next article, this time devoted to Jewish colonies.

The project was implemented thanks to a grant from the Minister of Internal Affairs and Administration.